Did a sexual revolution ever take place? In 2019, this magazine began publication with a manifesto reflecting on the half-century since the Stonewall rebellion announced the contemporary phase of what we now call the queer struggle. Then, we remarked on what was a revolutionary development in at least one sense: “the horizons which sexual liberationists were pursuing are now in some ways our ground.” We found the defense of these earthy horizons urgent, if insufficient, and called for the courage to pursue new ones. But in just four years, the ground seems to have shifted. Cracks now appear underfoot and something uncanny gropes its way out. Minor conflicts, in this light, can seem like foreshocks of an epochal overturning, bringing what once felt like certainties into question. Now it is no longer even clear what might be overturned.

Given the way some indicators are trending, we may soon look back on the present as the high-water mark of a certain form of sexual freedom. But the picture these indicators paint of this form is muddled. In the United States, for example, legal rulings which for decades shielded sexual practices from the state through enumerations of the right to privacy all seem to be coming up for hostile review, while more and more people find their way to depart from the sexual scene they guarded. Greater rates of queer or trans identification appear to define each younger generational cohort, while reported frequency of sexual activity has declined across the board. Some partisans of sexual freedom even take a projected decline in private car ownership, the extremely capital- and resource-intensive arrangement which required so comprehensive a level of coordination of class conflict, imperial violence, and metabolism of nature that it names an entire epoch of capitalist civilization, as a portent of the end. Without cars, “you don’t tend to do the things that teenagers do in the backseat,” the evolutionary psychologist Rob Henderson opined recently. A National Review blogger put it more bluntly: “Liberty (sex) and driving are intrinsically linked.”

This three-way equation of cars, sex, and freedom (or freedom as sex as a car) is certainly suggestive. But the proper name of the whole situation—the sexual conjuncture, we might say—has remained obscure. The enemies of the present know at least that it has gone too far. For them, sex today has lost the wisdom of restraint, which is what truly makes you sexually free. A recent roundtable on the topic at the Wall Street Journal invited a “reactionary feminist” to argue in favor of repression, perversely, on the grounds of pleasure. (“No more openness; more intimacy. Handwritten sexts by mail, or nothing at all.”) Here as usual, the position of reaction declines to articulate its own system of values, soothing itself instead with the promise that things will go back to the way they are supposed to be once the threatening present has been overthrown. Repression as a return to sexual freedom and pleasure after the catastrophe of too much of the same: this rhymes with the theorist Sita Balani’s recent argument that it is sexual freedom which throbs at the core of the modern political subject, the “ultimate truth of the sovereign individual,” lending all other values its distinctive flush.

The reactionaries do have an idea of the name of the present sexual regime: liberalism, by which they mean feminism, which they equate with an idea of the 1960s as a kind of licentious secular fall. In her The Case Against the Sexual Revolution, the British columnist Louise Perry alternates between “sexual liberation” and “sexual liberalism” to denote her antagonist: liberals are both the sex radicals who carried out this revolution and its current legatees. At moments Perry draws on Margaret Thatcher’s best-remembered statement to accuse the militants for women’s freedom of furthering a deregulatory agenda with regard to the sexual market. Feminists are “sexual Thatcherites,” because they act as if there is “no such thing as society,” in the sense that they conspire against patriarchal social restriction. This understanding of the relation of the ’60s women’s movement to the capitalist counteroffensive of the ’80s, a decisive turn of fortune in a jagged century of shearing planetary revolution and bloodthirsty counterrevolutionary slaughter, with cycles of proletarian thrusts which at points took the form of gender struggle and snarling counterinsurgency in the shape of the father, is worse than useless. But it is decisive for her argument. It conceals its unity with Thatcher’s project as articulated in the uncited coda to her infamous line: “There are individual men and women and there are families,” that is, the claims that the working class had ever managed to impose on the capitalist state would be shredded, and the costs for prosecuting a war against it exacted from the private wage-earning household as debt.

To the extent that Perry articulates a counterrevolutionary program, it is this. But as a mouthpiece for a certain fraction of the capitalist class, she does leave traces of helpful insight from her efforts. Though she doesn’t mention it, “sexual liberalism” is the concept that perfumes all of the French writer Michel Houellebecq’s rancid, influential body of work. His depiction of post-‘68 society as the wreckage of a utopian project which brought on a new, atomized hegemony distinguished by male sexual access to women has gained a broad reception, sensitive enough to the existence of social antagonism that readers can imagine they detect a kind of class analysis in it. With Houellebecq, as in other French novelist-philosophers of white genocide like Renaud Camus (the thinker of the “Great Replacement”) and Jean Raspail (author of The Camp of the Saints), an unmuffled shriek of wounded hierarchy travels internationally in their contemporary stagings of the rape of Europe. Self-styled dissidents from the racial and sexual order, these men accuse it of failing to prolong its line.

The repetition of such complaints even on the left is cause for some reflection. But more interesting is this resurrection of the race suicide discourse once common among the imperial ruling classes at the turn of the previous century, which simultaneously expressed a concern over the changing form of social relations between sexes. At stake was the reproduction of the white bourgeoisie, dependent on a dominating position within global production and exchange, which represented a sense of crisis to itself through supposed failures of breeding and diminution of something called racial stock. This self-consciously anxious sexuality, which took the form of new laws regulating legitimate births, sex work, miscegenation, or immigration of “sexual deviants,” soon experienced what contemporary observers then called a sexual revolution, “cracking open” the Victorian system of sexual morality in the early 1900s.

The idea of a sexual revolution as author of the present is perhaps the most popular historical concept of modernity at hand. But when exactly this revolution is supposed to have taken place is strangely mobile. Many invoke it to refer to the latest developments in sexual taxonomy or self-determination, though the charge still comes from its compressed summary of the 1960s. A contemporary survey from the Kinsey Institute was “confident,” however, in “asserting the absence of far-reaching changes in sexual norms in the United States.” If there was a sexual revolution of the 1960s, the researchers went on, “it apparently was not experienced by the great majority of women and men interviewed.” Meanwhile, the term itself was then at the ready because it had already emerged to capture a shift in sexual form roughly fifty years prior (as a 1964 Time magazine article on “The Second Sexual Revolution” had it: “Men with memories ask, ‘What, again?’”). Some of its more delirious critics place the hour of the sexual revolution even earlier, creatively fusing it with the French revolution of 1789 and placing the libertine Marquis de Sade, fresh from the Bastille, at its voluptuous head.

The promiscuous datings of this concept betray a different concern than historiography. In the Kinsey Institute report, the researchers suggest that there is a self-authoring effect from public speech about sex where “each mention served to sustain it further,” concretizing a topic of conversation into a “powerful cultural reality.” Perhaps. The debut of the phrase came amid a wave of “sex hysteria and sex discussion,” as a signal editorial put it at the time. But the question is what was there to talk about. In the early 2000s, the sociologist Göran Therborn compiled a centennial balance sheet of changes in family form, assessing and comparing the global state of legal patriarchy, marriage and sexual regulation, and family systems at the turns of the twentieth and twenty-first century centuries. If a revolution cleaved these years in two, how had it left its mark in law?

Therborn found evidence that the North Atlantic states and their satellites did experience a meaningful change in sexual conduct: a “lowering of the age of first intercourse” along with later marriage meant that “a long period for pre-marital sex, and a plurality of sexual partners over a lifetime” became normal, “in the statistical as well as a moral sense.” But this change was neither observed globally nor did it represent a fundamental historical departure: premarital sex was already “very frequent” in Western Europe before the early 1900s. It was European marriage rates, rather, that underwent a strange increase in the twentieth century.

The second third of the twentieth century was, in his tables, an age of “industrial marriage.” Not since the eighteenth century in France and Scandinavia or the sixteenth century in England had “such a large proportion of the population married,” Therborn notes. In the United States, nuptial rates of women between ages 20-24 underwent “a strong increase from 1940 to 1970” before a reversion by 1980 to rates last seen in 1900 and then a further decline. But none of the “dramatic cultural rebellions of the late 1960s” were reflected in the frequency of marriage before this later shift. “What should be underlined,” Therborn concludes, is that the middle third of the century “was a special period in modern Western population history.” The transition out of it was not an unprecedented decline of the family, but a “return to its modern historical complexity.” To the extent these rebellions had an effect on these pillars of sexual history, then, it was as a reversion to a previous norm. Their novelty was cast in relief by the end of an anomaly.

What most struck Therborn about the past hundred years instead was the fate of patriarchy. This was the true “big loser” of the century: its last quarter in particular saw “the most rapid and radical change in the history of human gender and generational relations.” The most widespread feature of the family in 1900 he surveyed—the law of the father—once determined practically every living person’s conduct in marriage, inheritance, household formation, schooling, etc., in variegated but near-universal form worldwide. And then it succumbed, in three acts spanning a century, to an equalization of formal rights in legislation if not in practice. Therborn seems to find some humor in reporting that the role of the communist movement was “crucial, if not overwhelming” in overturning this venerable tradition. The Bolsheviks undertook early revisions to family and marriage law in the teeth of civil war, setting an example for revolutionaries globally in the first third of the century; the first major legal reform promulgated under Chinese Communist rule was the Marriage Law of 1950, abolishing the “feudal marriage system.” And following the rebellions of the 60s and 70s, it was activist communist women who constructed the international agreements atop the armature of the UN to carry out global legal and economic reforms in the latter third of the century. But as Lenin put it in an address on the fourth anniversary of the October Revolution, the abolition of the inequality of the sexes was to be understood as an achievement of the bourgeois-democratic elements in the revolution against a “disgusting survival” of the feudal order which only Bolshevik legislation had been able to carry out.

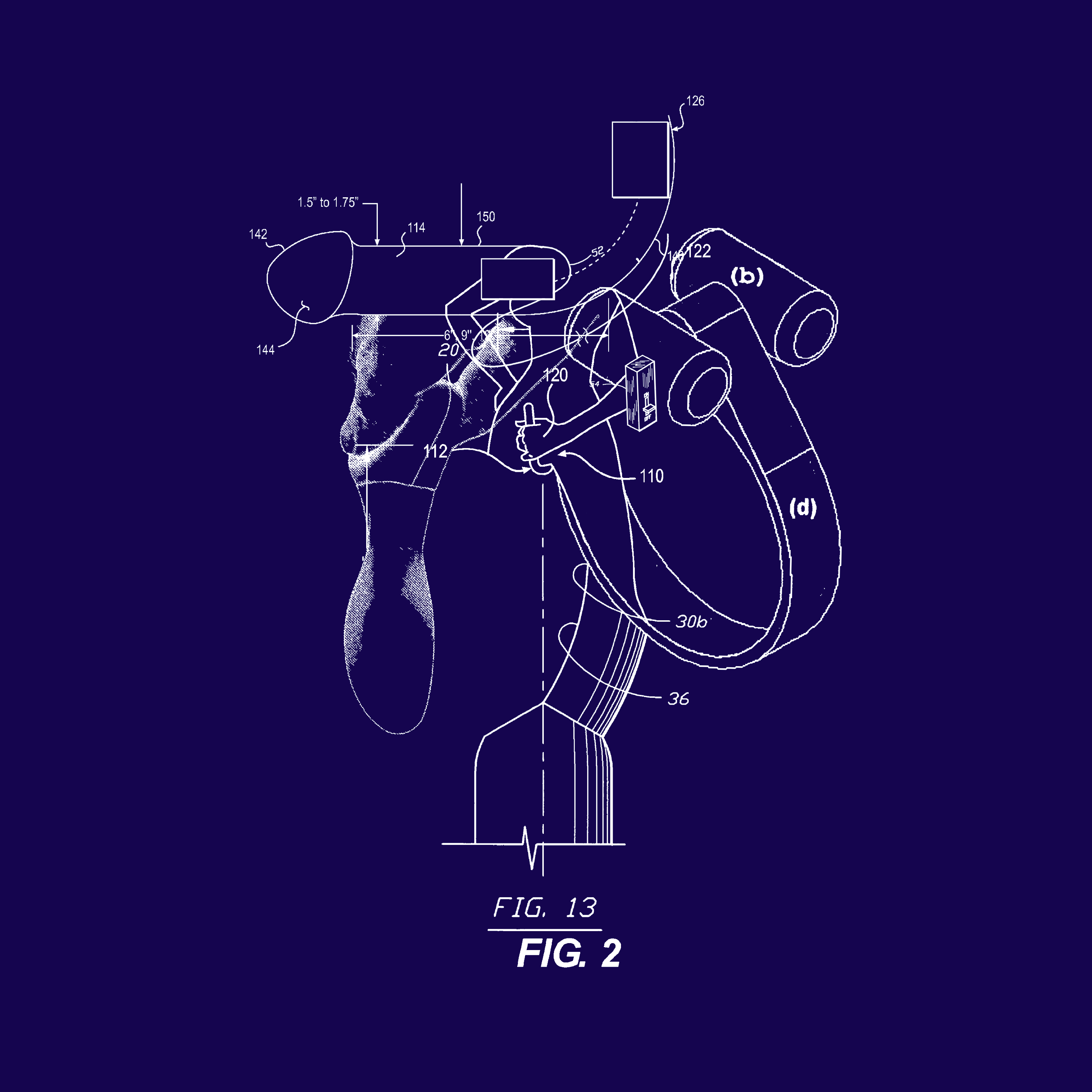

Formal sexual equality was a face of modernity, the work of the bourgeois revolution against premodern social relations, but it took the intercession of the communist movement to impose it in history. The admixture of this moment was captured by one of the greats of Soviet literature, Andrei Platonov, who in 1923 described the arrival of a new sexual form in his satirical pamphlet “Anti-Sexus.” Writing as the supposed translator of a brochure announcing the Soviet sales franchise of an “electromagnetic instrument,” a sex toy, Platonov warns the reader that they are holding an unsurpassed document of the bourgeois epoch’s “living decay, its utter moral atrophy.” The device itself (imagine a Machine Age vibrator or Fleshlight; there were two product lines) is promised to mechanically rationalize sexual pleasure, reducing the labor involved by half and thus freeing humanity for higher, more spiritual pursuits. “An unregulated sex is an unregulated soul; it’s unprofitable,” the pamphlet crows, closing with testimonials from global names like Henry Ford, Gandhi, Mussolini, Neville Chamberlain, Charlie Chaplin, and Keynes, nearly all praising the Anti-Sexus device for its humanity-liberating innovation in freedom from carnal pleasure.

The oddity of the short text aside (it was only published posthumously, in 1981, and in English translation not until 2013), it documents aspects of the capitalist sexual order that stuck out to a Soviet observer in the early 1920s. The device represents a compact monument to bourgeois decadence, of course, a classic object of communist invective: here is a gleaming, inhuman trespass into the tender zones of human existence. The prospect of Soviet adoption of this Taylorization of sex contributes to the tension propelling the satire. The ideological heterogeneity of its endorsers is part of the joke, but still barbed: Ford regrets he didn’t invent the machine himself, Chamberlain praises its help in managing “the hot-tempered colonial races,” Keynes calculates savings of a trillion a year, more “effective than any economic reform,” and Mussolini cites its emancipation of women “from the duties and the consequences of sex,” rendering them dearer assets to the nation. “Every member of the Fascists’ union is obligated to own an Anti-Sexus,” Platonov’s Mussolini decrees.

Illustrations by Emilio Martinez-Poppe

Illustrations by Emilio Martinez-Poppe

This strange satire on capitalist sexuality was a response to the arrival of something real. Platonov offers an insight about the politically unifying compulsions that offer an object to fascists, social democrats, imperialists, and racist industrial tycoons alike, jointly enabling the rule of capital: not pleasure, but its rationalization. Sex here is the literary form taken by the subordination of the living worker’s body to the imperatives of speed-up, fragmentation of the labor process, concentration, and mechanization that characterize the capitalist mode of production. It is also Platonov’s chosen register of resistance, touchingly ventriloquized by Charlie Chaplin, who sticks up for the “suffering, laughable, stuck-in-a-rut human being,” blowing “his stock of meager life-juice” for “a moment of fraternity with another derivative being.” This assertion of the worth of the mortal body against its abstract transcendence in a droplet of pleasure passed through the still of capitalist reason is a rough but accurate enough rendition of the Marxist critique of value, though the fictional translator’s hopes that merely publishing this bit of inhumanity might organize an “contra-antisexual” movement may be an object of Platonov’s satire as well.

The sexual form of capitalist society which Platonov has Keynes, Mussolini and Ford all agree on is presented as a historically novel social arrangement, shipped into human reality as a gadget. This arrangement can also be described as “sexual liberalism,” as the scholars Estelle Freedman and John D’Emilio do in their 1988 book Intimate Matters, which surveyed the development of sexuality across four centuries of settlement in the United States. Their use of the term appears to have made no direct impression on Houellebecq and company, though they speak as participants in the liberation movement the reactionaries set themselves against. The two describe sexual liberalism as the latest phase in a relay of hegemonic sexual forms: a “view of erotic expression” that contrasted with previous emphases on restraint through its beliefs in “heterosexual pleasure as a value in itself,” with sexual satisfaction “a critical component of personal happiness and successful marriage.” The banality or seeming self-evidence of these claims from the contemporary perspective is an indication that the situation they describe still obtains—and a measure of how sex works to naturalize the movement of history—but notice, these are the terms with which our reactionary feminist argued for a return to repression: pleasure and satisfaction as ends in themselves.

It is a sign of a social system’s durability when its critics adopt that system’s unique commitments as universal standards. Sexual liberalism departed from earlier modes of sexual thought and conduct, Freedman and D’Emilio argue, by detaching “sexual activity from the instrumental goal of procreation” and weakening the unity of “sexual expression and marriage” through the establishment of a youthful period of “experimentation as preparation for adult status.” Though they sketch its rise from the 1920s and announce its end as they write in the late 1980s, by the book’s second edition in 1997 they are content to merely “observe the continuing dissolution” of sexual liberalism in the face of a robust antagonist, the state-patriarchal sexuality championed by the religious right. In 2012, in the twenty-fifth anniversary third edition, no new judgment arrives. And it seems from the vantage point of 2023 that the main contours of this sexual form have in fact more or less persisted still, albeit somewhat modified in a dialectic with the position of reaction which it summons up. With Freedman and D’Emilio’s definition, then, we arrive at a round century of sexual liberalism, from the 1920s to the present, even if its future is in doubt.

A set of questions arises: What is the use of grasping this history of the twentieth century in these terms? Why link sexuality, already an infamously slippery political object, to a contradictory, possibly overbroad political category like liberalism? Why not discuss “sexual modernity,” as Balani does, or draw out the historicity of “heterosexuality” as a hegemonic form? For one thing, liberalism’s incoherence has the merit of accurately reflecting the kaleidoscopic profusion of relationships people have to the socially dominant form of sexuality as a political institution, while providing a name for what it nevertheless manages to uphold. As both a suite of personal dispositions toward capitalist society and a political project taking effective responsibility for its own reproduction, liberalism makes contact with each configuration of sexuality in this historical period. It denotes a sort of statecraft’s relation to class forces, well documented in zones where sexuality can be captured and shaped by practices like housing, zoning, loan underwriting, border inspection, etc. Liberalism can find affiliates in both revolutionary and recuperative political activity, whose confusion is also the hallmark of the history of sexual politics. And liberalism’s modern involvement in projects of race hygiene and imperial control also offers a term for the unity of race and capital in common notions of sex. But for our purposes, it offers a foil to communists who might wish to think more clearly about what elements of the present sexual world entail class society and, finally, what forms of pleasure and reproduction liberated from them might look like.

Thinking of sexuality as a moment of liberalism, a mode of apprehending capitalist society as divided into apparently natural spheres expressed by the state and the market, explains some of the confusion over the meanings of taboo, prohibition, liberation, and pleasure. After his wartime Los Angeles exile, Theodor Adorno returned to Frankfurt having made close observation of this midcentury sexuality and its industrial marriage from within one of its new leading economic zones. He characteristically finds in it a false freedom: “Talk of sexual taboos sounds anachronistic in an era where every young girl who is to any extent materially independent of her parents has a boyfriend; where the mass media, which are now fused with advertising, incessantly provide sexual stimulation, to the fury of their reactionary opponents, and where what in America is called a healthy sex life is so to speak a part of physical and psychic hygiene,” he writes in a 1963 essay, “Sexual Taboos and the Law Today.” This hygiene involves “a sort of morality of pleasure, a fun morality,” the experience of an illusion of liberation—but a necessary one, an illusion internal to the form of appearance social existence must take in capitalist society. If patriarchal mores of restraint have been made obsolete, now “sexuality, turned on and off, channeled and exploited in countless forms by the material and cultural industry, cooperates with this process of manipulation insofar as it is absorbed, institutionalized, and administered by society.” Far from having freed sexuality, bourgeois society after the wars has taken sexuality “directly under its control without any intermediate authorities like the church, often even without any state legitimation.”

Adorno sees an unmediated sexuality as both the threat to and what is threatened by the condition of formal freedom, the bourgeoisie’s ingenious solution to the problem of proletarian autonomy: political incorporation. Sex itself comes to represent capitalist social relations to those subjects who need to see their situation as naturally rather than politically constituted—that is, determined by market luck rather than conscious social control. Crucially, it expresses this social form through a concept which encompasses birth and desire, or fate and will. Sexual liberalism, then, would be an ideological form of expression taken by bourgeois social relations that represents these fetishistically as a sort of freely chosen nature.

This is a paradoxical concept, but it finds its historical counterpart in the characteristically modern form of breeding: eugenics. And the proximity of this infamous catastrophe to attempts at thinking sexual form which take the liberal separation of the political and the economic for granted can be seen in the early sexologist Magnus Hirschfeld’s 1934 monograph, Racism (supposedly the first published use of the titular term). Written in exile, the posthumous text is an astonishingly even-handed survey of modern race thinking. It is too generous to Hirschfeld’s enemies given his infamous status with the National Socialists, who declared him a public enemy, prevented his return to the country, looted his Institute for Sexual Science, incinerated its library in a pyre the photograph of which has become the standard image of Nazi book burning, and threw in an effigy of him for good measure. Hirschfeld traces the strain of thought from Count Arthur Gobineau’s aristocratic declinism to the National Socialists’ transposition of class war for race war, observing its rapid acquisition of respectability in recent years. “Seldom has a hypothesis,” he writes, “almost universally derided, secured such a multitude of zealous adherents within a few decades.”

Breezily dispatching attempts to anchor supposed races in biology, Hirschfeld nevertheless entertains the principles of amelioration or advancement among peoples while strenuously refuting the effective unity of the concept of race. He describes the National Socialist program for racial betterment as concealing a desire “to transform the German state into a ‘human stud-farm.’” This is a reference to the Nazi program of “conjugal selection,” a precursor of Freedman and D’Emilio’s anticipated post-liberal sexuality, where the state determines marriage arrangements which might previously have been the prerogative of the father had the bourgeois-democratic revolution not overthrown him. Hirschfeld observes, tepidly, that if “a serious endeavour is to be made to breed a race of Nietzschean supermen and superwomen, the Racial Offices should be promptly transformed into Marriage Advisory Boards, guided by hygienic and eugenist principles widely different from those upon which the present crude attempts at racist selection are based.”

Hirschfield’s sober presentation of the preparation for genocide has a jarring effect, not least because of the proximity of state eugenics to Hirschfeld’s own sexual reform efforts on the very page. He cites a discussion with the author of a 1911 American pamphlet titled “Socialism and Eugenics” on the “possibilities of human sterilisation for eugenic purposes.” This socialist writer shares that he was warned by a comrade about the danger of implementing such a program “before the social revolution,” as it will be used “by the possessing classes to sterilise their political adversaries as ‘undesirable types.’” Hirschfeld agrees this “gloomy forecast” has come to pass, his death soon to confirm his grim estimation of such danger. In a strange parallel to Platonov’s satire, the actual translator of Hirschfeld’s Racism was this very American eugenicist.

Through a maneuver similar to that with which liberalism disavows its reliance on violence to sustain its pretense of contractual freedom, the reformist racial-sexual liberalism which Hirschfeld articulated as a kind of antiracism still contained within it the principles of eugenic breeding. This equivocation preserved a concept of race hierarchy in the relations through which development and foreign aid went hand-in-hand with population control programs. And strains of the negative eugenics apparently discredited by the Nazi project have found ample refuge in the metropole’s liberal carceral system, targeting poor, disabled, Native, Black, or migrant women for sterilization up to this day.

Why would these attempts at conscious social control of sexuality find such frequent expression in now-discredited race science? At one level, capital is, as Marx puts it, indifferent to the reproductive status of individual laborers “as long as the race of laborers doesn’t die out.” For bourgeois social relations, sexuality is an impersonal question of relation to class society. Sexual liberalism takes the economic cleavages of the social and presents them as the outcome of private drives. It naturalizes the violence of the social division of labor as simply the issue of desire. For the liberal, sex is the form of appearance of larger social forces, mystifying their operation as nature. It is sex that bears the meaning of racial equality, and sex that explains and justifies the patriarchal arrangement of production and violence that structures the world. It was not without reason that the segregationists, who understood something fundamental about the capitalist economy, called communism “race mixing.” But equally, the complacent antiracism of Hirschfeld’s sexological “elective affinities” was nowhere near a revolutionary position. The mediating term which sexual reformers wished to seize in the process of social transformation proved to be quicksilver, pooling into the liberal proposition of formally free sexuality which only reproduces a more fundamental class rule.

It was the difficulty of the “sexual question” which prompted Antonio Gramsci to reflect on a situation of intellectual and moral confusion in his notebook from 1929. “I have heard that in Naples there would be an immediate rush of free-love advocates with their neo-Malthusian pamphlets, etc. whenever women’s meetings were held,” he wrote. These “ridiculous daydreamers descend upon the new movements” in moments of general disorder, and “it is necessary to create sober, patient people who do not despair in the face of the worst horrors and who do not become exuberant with every silliness. Pessimism of the intelligence, optimism of the will.”

That the incoherence of sexual reform prompted perhaps the most ringing communist declamation in a century full of them testifies, in a strange way, to its historical weight. A history of this program as entangled with the international communist movement in a close contrapuntal motion might itself follow the rubric “optimism of the intellect, pessimism of the will.” But such a history would require seeing the transformation of sexuality during the momentous twentieth century not as a libertarian unfettering of desire onto the market, but as a moment in the reproduction of the antinomy between it and the state. The impossibility of subjecting sexuality to conscious social control expresses this aspect of liberalism in the strict sense: the conceptual sundering of capitalist social relations into an autonomous market following quasi-natural laws, and a state which can deliberate over their effects but not their social constitution. If there was a revolutionary transformation of sexuality in the past century, it is in the sense that capitalist social relations are revolutionary, involved in an overthrow of patriarchal law and yet committed to reproducing liberalism’s planetary hierarchy of peoples.

A real movement which breaks with sexuality as the seal over a liberal separation of spheres is yet to come. What a communist sexual program might look like is still unclear, but it would at least have to overcome the liberal concept of sexuality which is a moment in the reproduction of class society. As sexuality mediates the appearance of social necessity in present society, so a communist sexuality would take place in a temporality liberated from such necessity—sex in free time. And this time cannot come too soon: as liberalism loses its historical footing, the fascist movement prepares its advance, confident in its conviction that it only expresses what capital truly desires. ⊱