ONE.

CIRCUMVENTION

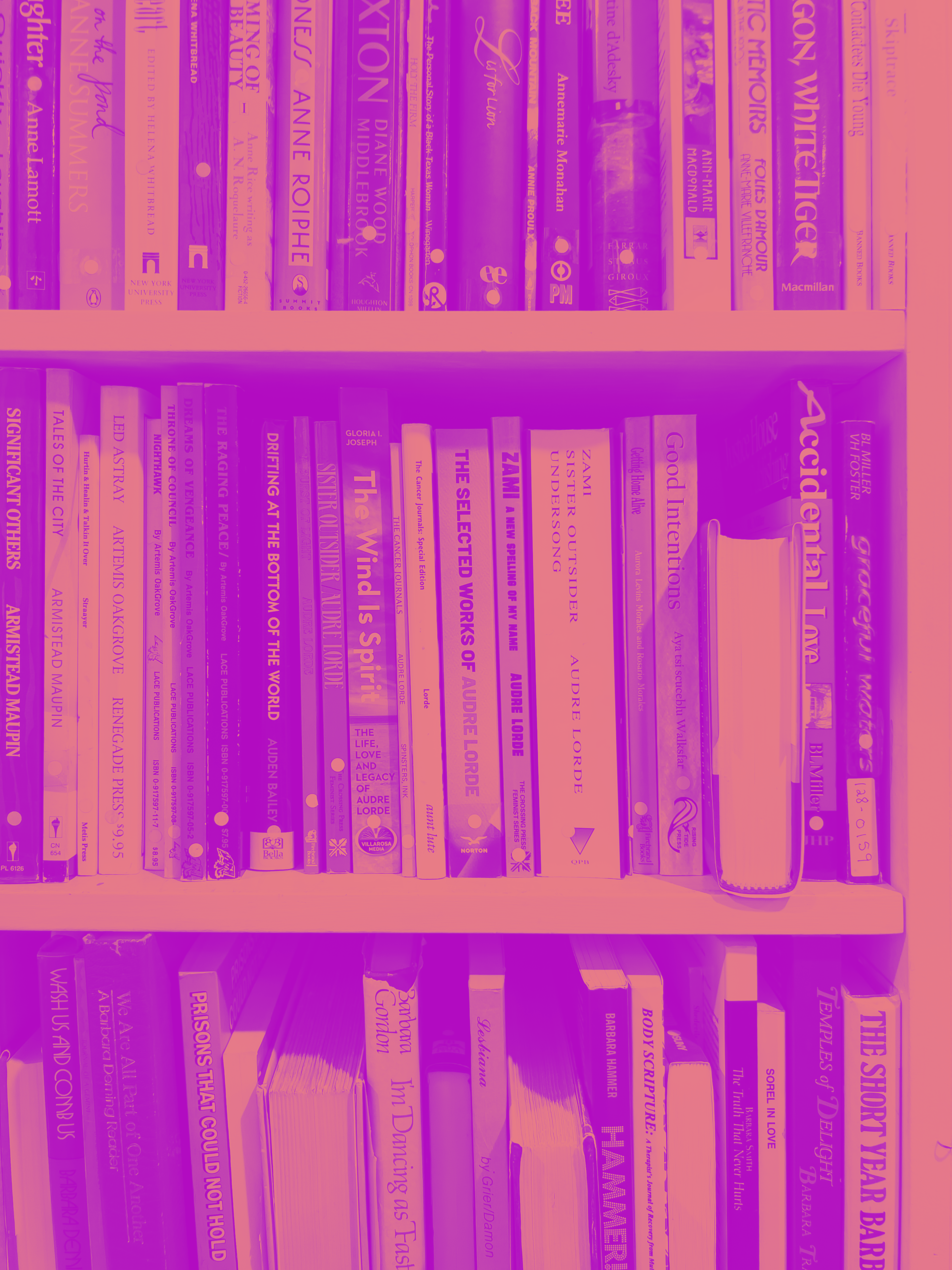

Photographs courtesy of the Lesbian Herstory Archives

Photographs courtesy of the Lesbian Herstory Archives

I like to think I’m a good reader, though I fear that the consequence is that I read too much into sex. I choke on words. Crude little gestures stick with me for weeks after a romantic encounter. Physical fumbles turn into refrains recited over and over in my head. Moreover, my early experiences with sex were less like mutual play and more like a story I didn’t have any hand in writing, even if I had consented. But it took me years (and feminist movements) to realize I hadn’t always.

In other words, I thought I was a reader of sex and not a writer of its scripts, a spectator and not a participant in its scenes. I thought this made me clumsy, awkward, unerotic, undesirable. A few years ago, those already unstable binaries would begin to further falsify. I was jerking off for hours on end every single day. I was in bed with myself, eyes fluttering, back spasming, toes cramping, breath shallowing, insides sighing, all the rest. But perhaps because there was no immediate presence of an other, I didn’t do much close reading of my conditions. Spending lots of time touching myself felt good enough, but combined with a series of events doctors call “symptoms,” my addiction psychiatrist felt he had a diagnosis. At that time, though not forever, hypomania—and the accompanying sexual compulsion—was a small mercy, a welcome relief from feeling coerced into racialized tropes of hypersexuality.

Since before I was born, black lesbian feminist writing has explored the connection between sex and everything else (whether racial capitalism, drug use, the medical industrial complex, childhood, the family, cisheteropatriarchal domination, or education). Emerging from a confrontation with state neglect, projected deviance, enforced abjection, and exclusion from dominant (hetero-masculinist) black communities, black lesbian feminist writing in the late twentieth century clarified the already existing scale, breadth, and immensity of a sexual-political economy that connects to all facets of life and death. When white feminists were arguing over whether or not the personal was political, black lesbian feminists wrote the political as sexual. Black lesbian sex, seen through literature and publishing efforts, was taken up as a theory and practice to critique heteronormative narratives and policies that siphoned off sex from political life.

In her 2019 book Queer Times, Black Futures, cinema and media studies scholar Kara Keeling describes her project as “less a search than a circumvention,” characterizing the latter as an opaque temporal organization open to interruptions. Attempting to allow for interruptions, what follows here is an attempt to reread late twentieth-century texts that invoke black lesbian sex in light of a state-rationalized predicament that coerces violent intimacies, while repudiating forms of (social) reproduction beyond the family. Around fifty years ago, as black queer people were denied sexual legibility on the level of politics, the law, and culture, they developed their own vocabulary of sexual abjection, deviance and gender non-normativity, literatures which gave experience to oppressive conditions without glorifying the power of sexuality. This essay is not so much about reading. More precisely, I am interested in narrating and even politicizing my own reading of black lesbian feminists who were themselves unafraid to read sex, writing about their sexual position and sex itself as aching and enfleshed. Circumventions involve avoidance, evasion, bypassing, nullifying—this is part of what black lesbian literature opened up. While in the past, I encountered the blossoming black feminist literatures of the 1970s, 1980s, and 1990s as idealized models of collective self-creation, this rereading helped me better understand that archive while also processing the loss and disappointment that had arisen from the last half-century or so of life-denying sexual histories.

I gesture to a history of struggle to contend not only with the political nature of sex but also with the sexual dimensions of politics. Sex is not positive. It’s real, it’s ambivalent. Sex encompasses pleasure, violence, taboo, harm, conflict, abuse. This essay, on the one hand, engages sex as a constitutive element of black lesbian literature. On the other hand, this essay makes a claim on the contemporary moment, arguing that, drawing from this prescient literature, sex is a connective tissue in all politics. We must continue to learn to read it. The stakes are not merely representation or culture or minoritarian aesthetics. The stakes are not even censorship, obscenity, and an ideology of purity but also genocide, reproduction, and survival. The stakes are life and death as we know it.

TWO.

DOES YOUR MAMA KNOW?

Black lesbian feminist writers such as Dionne Brand, Cheryl Clarke, Anita Cornwell, Alexis De Veaux, Demita Frazier, Jewelle L. Gomez, Jackie Kay, Audre Lorde, and Barbara and Beverly Smith (to name only a few of the more recognized writers) have long explored themes of sex, sexuality, gender, the erotic, the carnal, and the libidinal. Sociopolitical networks of black feminist independent publishers and editors underscore how anthologies, reference works, and archives are an especially important aspect in the making and preserving of their collective history. In this way, it is impossible to think any black queer literature without acknowledging radical black feminisms of the same period—The Black Woman: An Anthology (1970), Home Girls: A Black Feminist Anthology (1983), and Black-Eyed Susans and Midnight Birds: Stories by and About Black Women (1975). Additionally, the late 1970s publication Conditions, whose subtitle is “a feminist magazine of writing by women with a particular emphasis on writing by lesbians” is an important early example of an organizational practice that emphasized a working-class and multiracial conceptualization. Some of these publishing efforts were explicitly about sex and sensuality, for example, Erotique Noire/Black Erotica (1992), an anthology edited by Miriam DeCosta-Willis, Reginald Martin, and Roseann P. Bell that focused on the celebration of black erotics.

Collected in magazines, journals, zines, broadsides, pamphlets, and books including the exemplar Does Your Mama Know? An Anthology of Black Lesbian Coming Out Stories (edited by Lisa C. Moore, founder of RedBone Press) and the more recent Mouths of Rain: An Anthology of Black Lesbian Thought (edited by Briona Simone Jones), black lesbian writing more often did not center sex as a main focus. A Lambda Literary Award Nominee for Anthologies/Fiction, Afrekete: An Anthology of Black Lesbian Writing (1995) includes twenty pieces of poetry, fiction, and nonfiction culled from over two hundred submissions from emerging and well-known writers in English-speaking countries across the Americas, the Caribbean, Australia, and Europe. Co-edited by writer Catherine E. McKinley, along with screenwriter and filmmaker L. Joyce DeLaney, Afrekete is not explicitly about sex writing but the erotics creep in and soak up the space they are allotted. Literary fictions such as these granted readers and writers an exploration of desire that couldn’t be seamlessly lived out in reality but could live in the imaginary. Sex had a necessary place in the world of the literature, even if sex’s place “out there” was much more uncertain and elusive, anesthetized and brutalized. This tension reflects a cultural anxiety about how sex is deployed selectively and cruelly to manage these expendable and disposable lives that racial capitalism creates and maintains.

Even as anthologies index a coming together, they are also sites of conflict and difference. By drawing together multiple writers from a number of walks of life and political traditions (antiwar, internationalism, anti-apartheid, labor organizing, civil rights, reproductive justice, harm reduction, and more), they often register a range of arguments and perspectives. Anthologies also reflect a loss: what can’t be included, what can’t fit, what won’t fit. Anthologies in this period became literary records of fucking in a zone of (sexual) abjection. If the norm for black lesbian literature was the anthology, reading carefully into these publishing genealogies, beyond the representational, reveals a cluster of thinkers who understood their position as political and sexual. Reading was participation. Sex was participatory. Much black lesbian sex writing was not published in professionalized arenas and instead, it grew out of a community of readers and writers who identified or were identified as lesbians, queers, gays, bisexuals, dykes, studs, aggressives, bulldaggers, trans, and same-gender-loving people.

At the same time as this burgeoning cultural production, black lesbian thought and practice contended with erasure, absence, and silence. In the introduction to Afrekete, McKinley draws on Audre Lorde’s Zami: A New Spelling of My Name (1982) to highlight “the narrow nationalism, the strangling prescriptions of Black womanhood, and by extension, the homophobia endemic to the Afrocentric movement.” McKinley continues to describe her own shifting encounters with Zami:

I read with the furtiveness of my childhood, when I would stuff things in the gaps of the frame of the door to hide the light as I stayed up beyond decent hours, listening for my mother’s footsteps; feeling aroused and ashamed. I used a pen to highlight important text, often skipping over the explicitly “lesbian” passages. Unless sex was involved. Rereading Zami today, the places where there is an absence of markings is a truer mark of the book’s value for me [italics in original].

Here, toggling between absence and presence, the relation between reading and sex is not quite clear. But if sex was anything to McKinley it was an essential allure to the text. It couldn’t be skipped over, despite shame.

What I am frustrated by in McKinley’s telling, as an origin story, is that it fixes black lesbian thought, fetishizing the singularity of intellectualism and the exceptionalist genius of Lorde. McKinley literally describes Zami as a “seminal text,” that is the semen/the seed of “Black lesbian life drawn by an out lesbian writer.” Regarding the overdetermination of Lorde as the source of black lesbian literature, McKinley admits that “for too many readers, this was the first representation—or at best one of the very few.” And yet Zami—the title Lorde says is a “Carriacou name for women who work together as friends and lovers”—demonstrates the everywhereness of lesbian sex, a ubiquity almost mandated by antiblackness, heteronormativity, misogyny, and white supremacist capitalism.

Our elders saw injustice and suffering in invisibility or the paucity of representations of black lesbian desire. But they found sexual vitality represented in textbooks, under the rug, in their own diaries. In the 1988 essay collection Living by the Word, an amazed Alice Walker explained that erotica was where she first learned about same-sex desire. Though it might be easy to argue black lesbian longing builds a separatist fantasy, an alternative world, a place to imagine, the preservational impulse behind black lesbians’ turn to literature to record and archive indexes a libidinal-economic structure where black lesbian sex is squeezed out in favor of other conceptions of sex that are not so holistic, not so explicit in their critiques of family and reproductive politics.

Black lesbian literature had long been the source of an epistemological quandary—how to know sex—turned political demand—sex must be known. These lesbians knew the necessity of a literature that would leave nothing out. Responding to an antiblack, sexist, and lesbophobic publishing industry, black lesbian feminists sought to connect sex’s confrontation with and production of life. They couldn’t run from it. They wouldn’t. Sex was an urgent concern of this new Women Loving Women (WLW) or Same Gender Loving (per activist Cleo Manago) wave that recognized the bigness of sex, its capability for touching everything, for infecting mechanisms of control and invigorating social transformations. So while sex seemed epistemologically dominated by the medical-industrial complex, black lesbian writing in general and about sex more specifically demanded an encounter that was said not to exist: the encounter between thought and sex.

At the end of Zami, black queer cynosure Lorde’s biomythography (a form of her own invention), is a little fashion writing in all its melodrama, a cacophony of “beautiful Black women in all different combinations of dress.” In inventing her own genre, Lorde gets after the hotness of both stable binary genders and genders that don’t fit the binary. Her taxonomy, limning butch−femme distinctions, is a testament to the lust energized by clothing. Through thick descriptions—“garrison belts galore, broad black leather belts with shiny thin buckles that originated in army-navy surplus stores, and oxford-styled shirts of the new, iron-free dacron, with its stiff, see-through crispness”—Lorde sees fashion like traffic lights, controlling the ebbs and flows of flirtations and invitations. “Clothes were often the most important way of broadcasting one’s chosen sexual role,” she says. I can glimpse her abundance, her lovers, her shopping trips, her ornaments but I cannot grasp the climax.

Lorde was hardly the most explicit writer of sex during her time but her work was powerful and prevalent enough to be used as an example of obscenity by conservative Senator Jesse Helms, who wanted to cut public arts funding. (In 1992, in the dedication to Contemporary Lesbian Writers of the United States: A Bio-bibliographical Critical Sourcebook, Jewelle L. Gomez wrote that “it was [Lorde’s] provocative questions and her wide reach that terrified him and the religious right.”)

It’s worth noting that their analytics are not entirely suitable for our own historical conjuncture. While McKinley, Lorde, and Walker were writing through the disappointment of reversals of decolonization and civil rights, today we live in the aftermath of the failures of visibility and representation. I wonder, has the cultural practice of the 1980s and 1990s become bounded knowledge, sex repackaged as information? I mean, most of us barely even read Audre Lorde but claim her like baggage. (I hesitantly refer to Lorde’s writing multiple times in this essay because she is omnipresent in our contemporary LGBTQ+ discourse.) Moving with but beyond what these anthologies can offer is key. We must resist sexuality’s disappearance, leaving room for the pain and the pleasure, for sexuality to produce disturbances, rupture boundaries and emphasize contradictions. The conceit of today’s liberals, conservatives, far-right and well-meaning leftists alike is that they believe they can manage sexuality without exploring it, effectively dismissing the all-presence of sex.

THREE.

IN YOUR DADDY’S HOUSE

In 1989, black feminist activist and poet Terri Jewell began interviewing ninety-year-old black lesbian activist Ruth Ellis when she was living in Detroit, Michigan. Ellis died in 2000 at the age of one hundred and one and until then, she was referred to as the oldest known living lesbian. The interview between Jewell and Ellis would later be published in Jamaican Canadian writer Makeda Silvera’s A Piece of My Heart: A Lesbian of Color Anthology (1992). Jewell, who herself died before Ellis, in 1995 at the age of forty-one, asks Ellis if she was gay before the age of twenty-one. “Yes,” Ellis replies. “I used to fool around with girls and have them stay all night. One morning, my Daddy said, ‘Next time ya’ll make that much noise, I’m going to put you BOTH out.’ ” Jewell is shocked, half asking and half exclaiming, “You mean to tell me you were in your daddy’s house?!!!” Ellis, who said she never came out and that her family always accepted her, responds matter of factly—“Sure! That’s where I lived!”—as if fucking in your daddy’s house in the early twentieth century was the most ordinary act of all.

Amid the contemporary privatization and criminalization of both public sex and pseudo−public sex on the Internet, Ellis and Jewell’s exchange demonstrates that sex is everywhere. We must take its ever-presence seriously. Sex is everything and it is everywhere, even as, in the seams of public spectacle, it appears as both totally world-breaking and as undisclosed. More specifically, lesbian sex for Ellis was something like an open secret—hidden, discussed in code and comedy, but also ever-present.

Take prisons, for example, which are not routinely acknowledged as sites of immense sexuality. Inside, trans, gender nonconforming, and nonbinary identities are even more heavily governed by state power. People are separated and isolating according to regulatory categories and put into cages. Known as the first out black lesbian to direct a film (The Watermelon Woman, 1996), Cheryl Dunye’s 2001 TV movie Stranger Inside opens with the explicit prohibition of desire inside the walls of the institution. Family, friendship, romance, sex, violence, the prison, the church… it’s all there. The titular “stranger” is the protagonist’s mother, but also, perhaps, the stranger inside the protagonist herself. The protagonist, Treasure, is transferred to the same prison as her incarcerated mother. After a dramatized ecstatic and trauma-affirming reunion with Brownie, in the next scene Treasure is having sex in the chapel with her lover Sugar. The prison appears as an Oedipal mutation, an account of black lesbian sexuality that demonstrates its pervasiveness in institutions, in families, and in our psychic lives.

I bring up Ellis and Dunye, their invocation of the paradigmatic father’s house and the prison respectively, because the force of sex in our capitalist society draws heavily from its enforced secrecy. Sex is bracketed, demarcated, censored, made ancillary, and depicted by liberal feminists as an instinctual drive that is to blame for men’s violence. Ellis and Dunye’s interventions demonstrate the parallels between daddy’s house as a space where adolescent queer sexuality goes down and the prison as a space where queer communities define themselves. Whether sexuality in capitalist society and in the genocidal project called the United States is sanctioned or not, the relationship between the family household and queerness, and between the prison system and sex, is unavoidable and yet too often disavowed. Through gratuitous violence and the negation of care relations, the state maintains its power by organizing sex both in the home and the prison. We cannot talk about sex without disclosing a certain anxiety about sex, one so characteristic of the black lesbian response.

While beginning this essay on black lesbian sex and reading, I was uncertain about the intellectualization of sex; maybe that is part of the dilemma. In the progressive cosmopolitan circles of the global intellectual elite, the fullness of life is rigorously disavowed in favor of professional legibility. We regard thought as sexless and sex as thoughtless. Sex is where thoughtless thought takes place. Sex is where dominant ideologies are secured, and spontaneity is risked.

Instead of setting sex apart from our political goals and responsibilities, black lesbian life also demonstrates the quotidian gravity of sex: not only those feet touching under the table, those hushed drunken makeouts on the dance floor and those highly charged friendships, but also what Amia Srinivasan refers to as “sex as a pedagogical failure” in the context of teaching and professor−student relationships, all despite or in spite of an overall culture of sexual repression and oppression. Reading black lesbian literature, its bent toward the erotic, reveals the way sex’s putative divorce from sense-making obscures its cultural entrenchment, from casual homophobia and violence against trans and nonbinary people to the propaganda that interracial relationships are a salve for racist consciousness.

Contemporary debates about sex—is it a source of liberation? a practice of freedom? a space of violence? a tool of subordination? a politics of pleasure? a dangerous risk?—have preoccupied queer movements in the United States. I will hazard a use of the idea of “sex” to refer to a political and epistemological category within capitalism that, governed by the market and state power, shifts between being invisible and being invisibilized to the effect of reproducing the contours of life and death, meaning and nonmeaning, and the flashpoints when gender and sexuality are added and subtracted. Furthermore, sex is a cultural and political project, laden with hegemonic assumptions about its putative naturalness.

Black lesbian literature in the 1970s, 1980s, and 1990s (a time Jafari S. Allen calls the “long 1980s”) sought to reconfigure sex through its depiction and make their enforced invisibility real. In other words, for us today, black lesbian literature at the end of the last century might function as a pedagogical tool of struggle, teaching us how big sex is, how much sex bleeds into conversations with dad, the mundane brutalities of revolutionary battles, the cockiness of the vanguard, the metaphorics of pornography, the miseries of white voyeurism. At a time of profound sexual crisis, what if the task, then, was not even to liberate sex from violence but to confront it, to meet contradiction?

Enlarging the space of sex to include daddy’s house and the prison exposes the casual violence of the relationship between sexuality and the state, with its logics of authority, control, shame, and normativity. For black people, the private space of the family was never granted the supposed security, insulation or privacy that the private sphere was suggested to offer, in part because the black family in the United States has been subject to surveillance, intervention, and violence. If the family never existed as a family, only a pathology, there could be nothing private about it. This vulnerability—the black family-as-pathology’s openness to state violence—reveals how lesbian sex operates as an open secret in both the heteronormative home and state institutions, such as the prison.

FOUR.

SO FUCKING FUCKED UP

“Why am I so fucking fucked up over you?” asks interdisciplinary artist Jamika Ajalon in “Kaleidoscope,” published in Afrekete. “My dick was on hard, my tongue begging to taste.” Black lesbian literatures like Ajalon’s were part of an activist effort to unleash certain kinds of experience into discourse. Gender and sexuality are not fixed, they insisted. Reading books that turn one on also requires a recognition of getting turned off: the ugly politicization of “bodies” in publics to which they don’t belong.

As Angela Davis wrote in her 1981 book Women, Race and Class, highlighting a libidinal economy tethered to the master−slave context,

The fictional image of the Black man as rapist has always strengthened its companion: the image of the Black woman as chronically promiscuous. For once the notion is accepted that Black men harbor irresistible and animal-like sexual ways, the entire race is invested in bestiality.

One might also add that the black couple (read: the black family) has also always strengthened its antithesis: the black gay. However, the structural queerness of the black family does not preclude black lesbianism’s vexed belonging. For once the black family—before and after the Moynihan Report—is written as pathology, its aberrations become not historical formations of their own but further proof of that aberration. In the context of this gender-neutral controlling fiction (to use a term from Patricia Hill Collins), this myth of the hypersexual black, black lesbianism isn’t about identity or choice as it is further evidence that the black woman does as she does: she fucks around. As scholar Matt Richardson writes in his book, The Queer Limit of Black Memory: Black Lesbian Literature and Irresolution (2013), “Representation of a normative resolution to the question of Black familial pathology requires the suppression of any echo of queerness.”

Literature is a critical medium for sexual encounters and entanglements, for going too far and not getting enough, for risk and imagination. How did this countercultural literature survive under such conditions? It’s amazing I get to read any of it today. We, in the present, continue to live with the ghosts of that time. The sexually conservative eighties tend to be memorialized by an onslaught of social, political, economic, global, and technological changes rather than as a time of robust forms of reading and activism. When it comes to the spectacularization and Hollywoodization of domestic politics, recall that in 1992, the conservative magazine American Spectator alleged that Anita Hill was a “lesbian acting out,” as if that was certainly worse than Clarence Thomas’s sexual harassment. Five years later, Angela Davis came out as a lesbian in OUT Magazine. Around the same time, Cathy Cohen’s notable 1997 essay “Punks, Bulldaggers, and Welfare Queens: The Radical Potential of Queer Politics?” demonstrates not only the coalition politics possible in queer marginalization but also the way one can be both a bulldagger and a welfare queen. Black lesbian mothers were increasingly vulnerable to state abandonment projects, urban ruin, and reproductive violence and regulation. All the while, mass incarceration skyrocketed, clearly affecting black lesbian communities, and many women, transgender men, and gender nonconforming people were locked up for not properly adhering to white supremacist gender categories. Black lesbian drug users, too, were harmed by the dismantling of the welfare state. Furthermore, black women, including lesbian women, are still invisible in the stories we tell about HIV/AIDS, as it has been wrongly painted as a disease solely affecting gay men. Of course, lesbians were diagnosed with HIV and they died of AIDS, and their labor (political organizing, nursing, care-taking) was an absented presence. As Marcus Lee told Jafari Allen, “The 1980s is often theorized as a period of Black political declination and deinstitutionalization—as a tragic lack—but, this view is tenable only if the framing excludes Black transgender, lesbian, bisexual, and gay male activists.” In other words, emergent and experimental thought of the 1970s was repoliticized by Reagan’s right, which weaponized the state to manage, discipline and discard deviant sexualities and racialized others.

“Combining responsibility for my body and my desire for political representation has been a continuous learning process,” writes sex worker, ACT UP member and Clit Club party organizer Jocelyn Maria Taylor in “Testimony of a Naked Woman” (1994). “My survival instincts have always surfaced through the more physical side of my self, maneuvering, twisting, and contorting my way through to the other side of whatever problem I was facing.” Instead of shying away from sex’s relation with thought, black lesbian literature digs deeper. Black lesbian cultural production registers what does not appear, what cannot appear, what refuses to appear. In this phenomenological conundrum, the explosion of literature by black women in the 1970s, 1980s, and 1990s also coincided with the increasing globalization and financialization of capital accumulation, and its attendant liberal multiculturalisms.

The geopolitical was the personal. The situation was international. The mass death and devastations of the HIV/AIDS epidemic demonstrated that there was no separation between political and sexual life. Many people in the United States were organizing, including against apartheid. In South Africa, the first pride march took place in Johannesburg in the early 1990s and was organized by the Gay and Lesbian Organization of Witwatersrand (GLOW), founded in the 1980s by anti-apartheid activists Bev Ditsie, Linda Ngcobo, Simon Nkoli, and others. For Nkoli and others, the end of apartheid and sexual freedom were connected fights. Notably, the post-apartheid constitution was the first in the world to outlaw discrimination on the basis of sexual orientation, establishing legislative protection for gay rights in South Africa.

Elite-driven structural violence against black lesbians also indexes violence against black women, black trans and gender nonconforming people, black poor people, and black people in general. As Farah Jasmine Griffin notes about the history of black women’s literature in general, “From the beginning, brilliant black lesbian feminists have been central participants in the articulation of black feminism.” There is another essay to be written about the ways black lesbians have been erased from shared intellectual and political histories. To state it plainly, the Combahee River Collective Statement, the radical document of black feminist socialism credited with the first deployment of the phrase “identity politics,” is not often remembered as a lesbian text. Then again, consider how the Black Lives Matter movement gained some radical currency because of the sexual identity of its founders. When, despite their identity, Black Lives Matter failed to address the particular suffering of black women (their vulnerability to state violence, not to mention their own spectacular forms of murder by police, as well as class, disability, and transgender identity), #SayHerName emerged as a supplement.

In our time, sex is clearly and brutally under threat. As black queer and trans people are under attack, much of liberal discourse skips over not only the violence (ignoring discursive pretense as violence) but also sexuality—in favor of a continued focus on diversity, celebration, and corporate recognition. This too is a kind of violence. As I write this sentence, the Anti-Homosexuality Bill, which criminalizes both LGBTQIA identities and sexual acts, was signed into law by Uganda’s President Museveni just a few days ago, on May 29, 2023.

Because of the grimness of our political circumstances, I am less interested in writing a banal lineage (BLM was founded by queer women!) where black lesbians, trans women, nonbinary people and queers have contributed to social movements, intellectual practice and literary formations. Rather, at the heart of my essay is an interest in where black lesbianism cannot fit, where their literature exceeds and overflows its own already unstable archive. In “Dyke Hands,” for instance, SDiane Bogus writes,

those hands you see folding laundry at the local laundrymat, reaching, grasping, holding canned goods at the supermarket, may very well be the genitalia of some womon’s lover, exposed… we suck with reverence the hands that bring us to knotted heat, the very hands that hours before were signing some assinine form or holding a steering wheel.

Bogus makes visible the sexual possibilities of supposed nonsexual encounters, the way desire is linked to everyday social life.

The (in)famous 1982 Barnard Conference on Sexuality, a momentous event in the sex wars with over 800 attendees, was themed “women’s sexual pleasure, choice and autonomy.” Later published as “Interstices: A Small Drama of Words,” at the conference literary critic Hortense Spillers described black women as “the beached whales of the sexual universe, unvoiced, misseen, not doing, awaiting their verb.” And so what would it mean, putting Spillers’s criticism and Bogus’s literature together, in this already abject sexual universe, to love another stranded being? I mean to say that whatever “empowerment” or “agency” that is possible here has passed through or exists within this sexual universe in which black women are the beached whales, sick or wounded ashore.

While Spillers was discussing black women in general, beached whales is a moving metaphor for the profundity and promiscuity of black lesbian sexuality that does not lose sight of the gender fluidity of black being, and the relation of antiblackness to the logic of sexual difference. Love between stranded beings seems to be a contradiction or an impossibility. Washed up on the shore, these beached whales of the sexual universe are not able to be seen, only, as Spillers writes, “misseen.” But in a phobic environment, these stranded beings, these non-sovereign figures, risk not only strategy but the sincerity of love—not simply between themselves but also, inside themselves, captured in sexual interiority. Perhaps there is nothing to see there. And literature is a way of seeing what’s not there.

In Bogus’s scene of the laundromat, holding hands might as well be as explicit as genitalia exposed, collapsing forms of affection, attachment, risk, and everyday life that often shapes the experience of sex. The various complementary itineraries brought up by Bogus and Spillers requires an attunement not so much to the politicization of sex but the awareness that sex has already been political.

FIVE.

HER HANDS ON ME

It’s Wednesday, one of those fresh metallic mornings. Outside is cold, yet warmer than it should be this time of year. I haven’t had sex in months and I remember, as Jewelle Gomez writes in “Piece of Time,” how “her hands on me and inside me pushed the city away.” Even still, sex is all over the seams of the urban landscape, exterior and interior, macro and micro. I find letters I had written to lovers that I never end up sending:

Some time around American Thanksgiving I realized I wanted you to be my girlfriend. Wait. Don’t stop reading because this isn’t about that. Like, I come across “sex writing” in the weirdest places. That’s because it’s not a thing you seek out, like porn. But I’m not writing this to get off. I’m writing this to remember all the times I got off, to think of all the future times I might get off. I remember being terrified when I was on top of you, when we were exchanging pressure. What I mean is that, at the end of the day, after we fucked more times in a weekend than I could count, is that it ended up not to matter how you actually felt but how I remembered how you felt, how I thought you felt, how you thought I felt. Right, I mean, it was kind of fucked up, our clothes mostly on but kind of off, with those other people around upstairs, like, am I making any sense? Are we making any fucking sense? Do language and sex meet? Forgive me but what is the communicability of our fucking?

By this time, the outline of our encounter is still engraved in these notes I have lying around. Embarrassed at my own attempts at love letters, part of me wondered if things were better off in fragments, without narrative, without closure, without character. What I register as a certain level of corniness in black lesbian sex writing communicates a desire for consumption or completion. Take Liza Wesley’s “Class Reunion,” from Does Your Mama Know?:

“I want to make love to you,” I told Barbara.

She regarded me with eyes aglow. “Suppose I want to make love to you?”

“Wait your turn.” I pushed her onto the bed.

The phrase “make love” is far too sentimental, even when queered. A reader like me refuses the difference between fucking and love-making, cringing at the love assumed in making. Love-making seems tethered to the straight imagination. But look, sometimes I still just can’t resist something like “We had one more night,” from Kathleen E. Morris’s 1996 book Speaking in Whispers: African-American Lesbian Erotica, published by Third Side Press, a small publishing house of lesbian fiction and women’s health founded in 1991. Mostly, though, we might land somewhere on the spectrum between one night and forever, between my girlfriend and not my girlfriend, between fucking and love-making that further illuminates the everywhereness of black lesbian sex. By between, I also mean a condition of connecting, linking, and joining that is also produced by tension.

SIX.

NO SEX

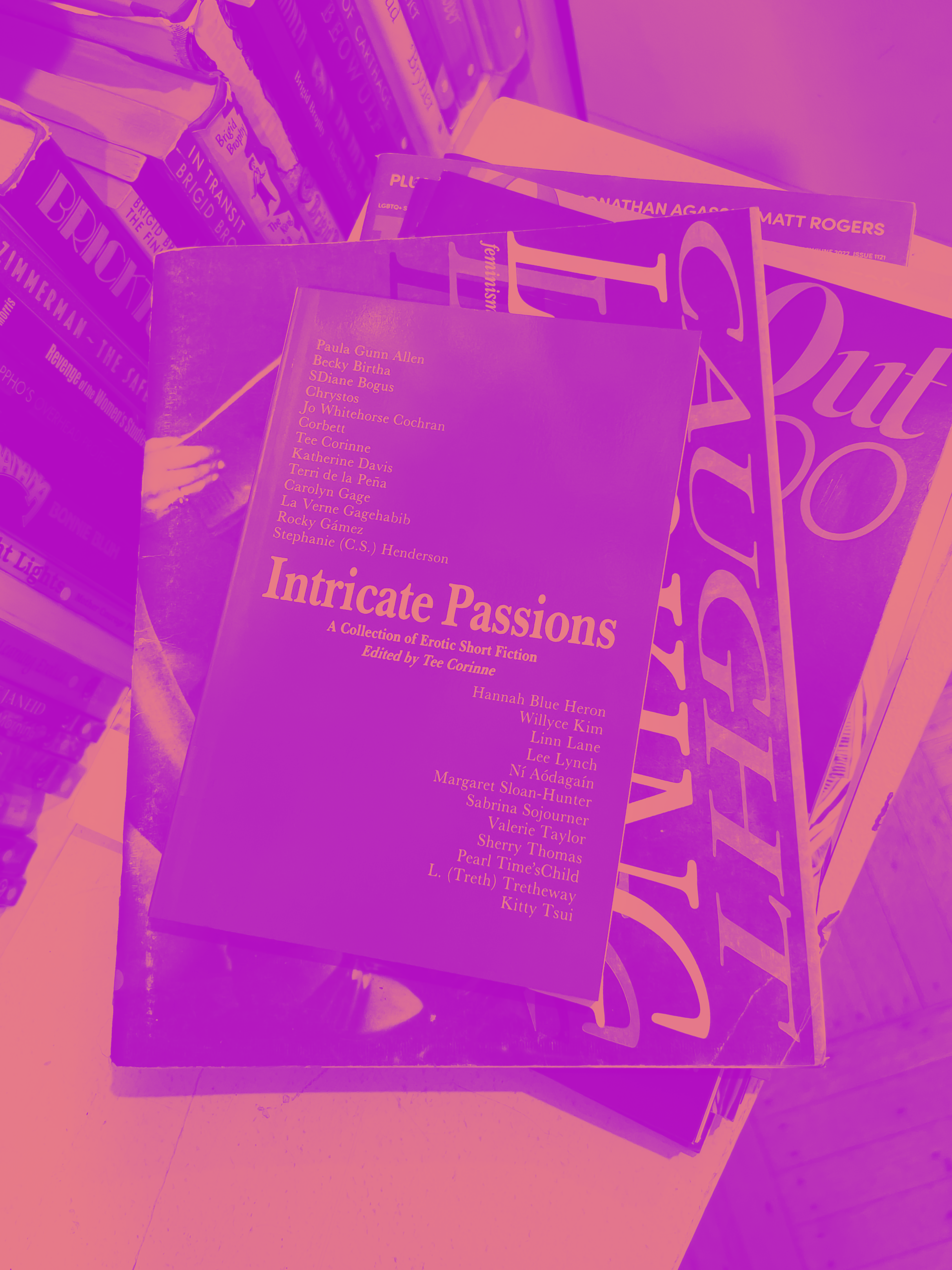

“If you’re reading this story because you think there’s going to be some sex in it, forget it,” Becky Birtha writes in “No Sex,” published in Intricate Passions: A Collection of Erotic Short Fiction:

I haven’t had any for three years. And I wouldn’t write about it if you paid me. This is a story about a bus trip to Washington for a demonstration—a solid, down-to-earth, serious subject. Shoe all your wild fantasies aside. You know as well as I do that nobody can really do anything on a bus anyway.

Psychoanalytic traditions have insisted that sex (or the libido) is so capacious and so inherent to the idea of being alive, that delimiting where it starts and where it ends is utterly impossible. What Birtha gets after is the sense that in erotic writing, the sex is framed as feminist common sense and often liberatory. And if something like liberation ever comes, it will require a messy struggle over sex.

Austin, Texas performance artist Sharon Bridgforth intensifies the orality and aurality of the erotics of the black rural South by writing it down in the nonlinear poetics of The Bull-Jean Stories. She’s not writing about sex but there’s sex to be found in these pages. In between, “you been fuckn!” it’s the quotidian, it’s:

every day

5:30am

bull-jean slip out

look ruffled

And Gayl Jones’s novels are sexy in spite of or perhaps because of their exploration of the histories and presents of slavery, trauma and abuse. The psychic mess of sexuality involves a certain amount of porousness—a knowledge of having been harmed and violated. In Eva’s Man, for instance, the protagonist ends up in jail for castrating her boyfriend as an act of retributive justice. There is no “post” in this trauma. Taking sex as an analytical opening, Birtha, Bridgforth and Jones bring to light how sex ceaselessly exceeds the demarcations to which sex is confined.

The excruciating pain of Jones’s writing, its scorched-earth method, reminds me of days when the only medicine for my debilitating migraines is cumming. (In 2013, the official journal of the International Headache Society published a study that argued that “sexual activity” relieved migraine and headache patients.) All that to say, in and out of sleep, some days the sickbed is the sexbed. (I can’t ever forget that Zami was published four years after Lorde was diagnosed with breast cancer at the age of forty-four.)

I began with Lorde’s Zami and end with her, too, despite the feeling of cliché, of playing a part. In Lorde’s 1978 essay “The Uses of the Erotic: The Erotic as Power,” originally given as a paper at Mount Holyoke College, she puts it plainly: “The erotic cannot be felt secondhand.” The conservatives and the fascists alike know that sex is a terrain of struggle: abortion, sexual assault, medical care, the family, political education. “The Uses of the Erotic” offers a political strategy for encountering reality at the same time as detaching oneself from a monstrous world. “Our erotic knowledge empowers us,” Lorde writes. It “becomes a lens through which we scrutinize all aspects of our existence, forcing us to evaluate those aspects honestly in terms of their relative meaning within our lives.” Lorde made it clear that the erotic was not the sexual. She was not a fan of pornography, as it “is a direct denial of the power of the erotic, for it represents the suppression of true feeling.” Seldom does Lorde torment her reader with sex. In Lorde’s quasi-utopic quest for empowerment here, she sometimes loses sight of power itself. In other words, Lorde tries to suck the sex out of the erotic. More contemporary uptakes of Lorde have elaborated on Lorde in order to make a distinction between positive sex (coded as affirming and healing) and negative sex (including BDSM, kink, porn, and other forms of sex work). In this essay, rereading a diffuse, heterogeneous yet interconnected archive of literatures by black lesbian writers in the United States, I have insisted on an interpretation of sex not only as the erotic but also as that which is not erotic at all, renewing the relationship between politics and sexuality.

Of all my fantasies, that of self-sufficiency is the most ruthless, even dangerous, the least sensual, and yet the most persistent. But maybe I dream of autonomy. One cool morning in April, I’m lying in bed with the window cracked. It’s the umpteenth hour of the Covid-19 pandemic. Last night on the telephone, I told a man, I’m fine, I cope well in isolation. Today a woman I used to sleep with checks in on me over text. I don’t tell her my father is dying. After a few afternoon debauches of masturbation as depressive reckoning, a fire in me is lit at even her most platonic hello. And then a wave from my gut to my fingertips. Time is moving this way, catastrophically and unevenly. Somewhere between touch and temperance, I can’t deny what Saidiya Hartman wrote, in The Los Angeles Review of Books in April 2020, that “huddling together, rather than isolation, is how we usually live and survive.” ⊱